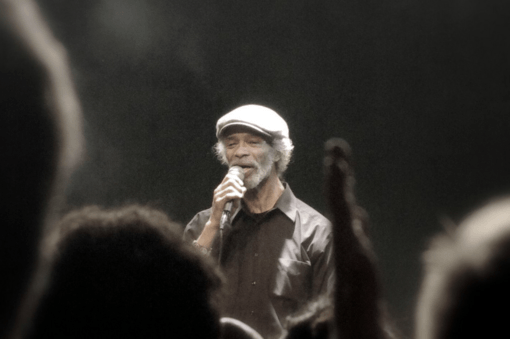

Photo source altemark | CC BY 2.0

The performance artist and jazz poet Gil Scott-Heron was wrong when he said in 1970, “The Revolution will not be televised.” But perhaps he was only wishful thinking and expressing what he wanted and not what he actually saw and heard around him.

More likely, he was being ironical and commenting on the wacky world of mass communication.

You can still appreciate Scott-Heron’s irony in lines like “The revolution will be brought to you by the Schaefer Award Theatre and/ will not star Natalie Wood and Steve McQueen or Bullwinkle and Julia/ The revolution will not give your mouth sex appeal.”

Scott-Heron died seven years ago at the age of 62. His many fans still revere him and appreciate his unique artistry on albums such as Pieces of a Man and Winter in America.

In fact, the cultural and political upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, from Selma, Alabama to Woodstock, New York, were taped, filmed, recorded and broadcast. Those who were alive in 1968 and who were glued to their TV screens saw the “police riot” in the streets of Chicago. They also heard the demonstrators chat, “The whole world is watching.”

That was an exaggeration. The whole world wasn’t only or just watching Chicago. It was also watching Prague and Paris and other hot spots of rebellion around the globe. But Americans often like to think that they are at the center of the world and that everyone in the world watches the U.S. Just how fallacious that notion is, is apparent to anyone who travels in Europe, Asia and South America and sees that the news isn’t only or just about Donald Trump and the White House.

In 1789, revolutionary Parisians stormed the Bastille because it had guns and ammunition. In 2014, pro-Russian forces seized the TV station in Donetsk, turned off Ukrainian TV and replaced it with TV channels from Moscow. They knew that TV today is far more potent than a tank or a jet plane.

Yippies such as Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin and Paul Krassner had that insight 50-years ago.

It wasn’t just the major television networks that captured scenes of the revolution in the 1960s and 1970s. The rebels photographed themselves. Newsreel, the radical filmmakers’ collective, documented the protests of the 1960s, and distributed their movies around the country.

In Santa Barbara, after a screening of The Columbia Revolt protesters burned down a branch of the Bank of America. No doubt about it, film and TV helped to ignite riots and rebellions. That’s why the Yippies, also known as the Youth International Party, staged irreverent events at the N.Y. Stock Market and elsewhere for the purpose of being filmed and then aired on TV. To Abbie Hoffman images alone, without words, conveyed powerful messages.

To the Yippies, Chicago in the summer of 1968 was a scenario in which everyone played a part in accord with an unwritten script that followed a logical sequence. Indeed, Chicago in 1968 was the culmination of the Theater of the Absurd.

The TV networks and the politicians learned from Chicago in 1968, and from televised images from Vietnam. They got smarter, and learned not to broadcast atrocities of war that helped to generate anti-war protests.

Fifty years after Chicago, everyone with a cell phone is a cinematographer. Citizens routinely capture on film police officers beating, shooting and killing unarmed black men. Phones and their photos have educated millions, and not just in the U.S. but in Egypt, China and Russia. No wonder the powers that be want to control the Internet and to censor words and images.

Of course, images alone won’t stop the police from lawlessness, though they can save lives.

If you have not heard Gil Scott-Heron perform “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” or if you want to hear it (and see it) again, you can find it on online. It still works as satire and as a brilliant piece of the spoken word that inspired a generation or two of rappers and hip-hoppers.

The names have changed since the 1970s when Scott-Heron sang, “The revolution will not show you pictures of Nixon/

Blowing a bugle and leading a charge by John Mitchell/ General Abrams and Spiro Agnew to eat/ Hog maws confiscated from a Harlem sanctuary.” But his sense of moral outrage still rings loud and clear. Substitute new names and the piece is as relevant as ever before.

Televised or not, revolutions will not be denied.