Last June the United States became the only nation to withdraw from the United Nations Human Rights Council, which a Trump official called a “cesspool of political bias.”

Just one day earlier, the U.N. Human Rights office had called Trump’s detention of children at the Mexican border “unconscionable.” Three days later, when the U.N. rapporteur for extreme poverty and human rights delivered a scalding report on the United States, Trump’s envoy to the United Nations assailed that report as “biased,” “politically motivated,” and “patently ridiculous.”

Since then, the world has been treated to the spectacle of refugees, many of them children – some still in diapers – sprayed with tear gas by U.S. border agents.

George Orwell would not have been surprised. It is a little known fact that Orwell, renowned for Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, defended the human rights of children and detainees with force and insistence. Indeed, his views strikingly anticipate U.N. views as expressed by Philip Alston – the author of the report blasted by Trump’s outgoing ambassador to the U.N., Nikki Haley.

What Orwell said on this subject over 60 years ago closely resembles the views that so infuriate Trump today. And a new archival discovery shows that, besides speaking up for children, Orwell took practical steps to build a new human rights movement that placed the needs of children front and center.

I learned the latter fact from a text I call “Orwell’s manifesto.” That text, which I found in a dusty archive, was drafted on January 2, 1946, six weeks before the U.N. inaugurated its Commission on Human Rights. And what Orwell proposed was far more dynamic than anything the U.N. Rights Commission would pursue for many decades.

Writing in dialogue with two of his friends, the novelist Arthur Koestler and the philosopher Bertrand Russell, Orwell called for the creation of a new international human rights organization. This group would unite human rights activists in Italy, France, Britain, Mexico, the United States and many other places. Orwell felt that the main established human rights groups had sacrificed their moral authority by defending Stalin’s 1936-1938 purge trials. What was needed now, he wrote, was a league that would resist any and all violations of democratic and human rights, “whether they occur in the British Empire or in Russian occupied territory.”

He considered calling this group Renaissance.

Orwell wanted to defend social as well as political rights. Democratic freedoms were of course fundamental: “habeas  corpus, freedom of speech and of the press, the right to political opposition and absence of political terrorism.” And yet, at the same time, “without equality of opportunity and a reasonable degree of equality of income, democratic rights have little value.”

corpus, freedom of speech and of the press, the right to political opposition and absence of political terrorism.” And yet, at the same time, “without equality of opportunity and a reasonable degree of equality of income, democratic rights have little value.”

Concretely, Orwell proposed three guiding aims: to guard “against economic exploitation”; to resist “the fettering” of anyone’s creative faculties; and, most distinctively, to ensure “equality of chance” to “every newborn citizen.”

Focusing on children in this way striking way was anything but ordinary. Orwell had adopted his infant son Richard not long before, and he wanted to remind the world that equality of opportunity is a hollow phrase unless it is accompanied by a commitment to “equality of chance” for every child, from the very first day of life.

The difficulty of achieving this goal was undeniable – a difficulty compounded because “there has grown up a certain contempt for democratic traditions.” But Orwell resisted paralyzing pessimism. He hoped that “men and women of all parties, races and creeds” would join him in the defense of these principles.

“We are sending you this rough draft,” Orwell told his intended readers, “to hear your reactions” – and, he added, “there is only one type of reaction that we are not anxious to hear: the answer that it is too late, that the evil has gone too far and can no longer be stopped by the methods visualised here.”

“‘Too late’ is the motto of escape into destruction.”

Just months after drafting this manifesto, Orwell spoke at a rally to protest the detention of 226 Spanish anti-fascists who had been interned in Lancashire after fleeing forced labor camps in Nazi-occupied France. Bureaucrats had imprisoned these Spaniards in camps with their former German captors, and they intended, before long, to deport them from Britain, penniless and against their will.

The police reported that 190 people heard Orwell oppose this policy of forced detention and repatriation. The spirit of the rally was evident in the title of a typescript written for the occasion by the organizers: The First Men to Fight Fascism are the Last to Secure Their Freedom.

Fast forward to 2018. Special Rapporteur Philip Alston isn’t George Orwell reborn, but his U.N. mission – to pair the defense of rights with the eradication of poverty – resembles Orwell’s goal. “Economic and social rights must be an important and authentic part of the overall agenda,” Alston says in his June 2018 report. He has upheld this position faithfully since he was appointed rapporteur, writing, upon his appointment in 2016, “that a surprisingly small proportion of self-described human rights NGOs do anything much on economic and social rights.”

When Donald Trump withdrew from the U.N. Human Rights Commission, Alston presented findings on rising poverty and declining democracy in the United States. In response to the claim that the Commission was a “cesspool,” he replied, acidly: “Speaking of cesspools, my report [stresses] those…I witnessed in Alabama as raw sewage poured into the gardens of people who could never afford to pay $30,000 for their own septic systems….”

Alston’s full report is unreservedly critical. “The United States has the highest income inequality in the Western world, and this can only be made worse by the massive new tax cuts overwhelmingly benefiting the wealthy. At the other end of the spectrum, 40 million Americans live in poverty and 18.5 million of those live in extreme poverty.”

Children, to a massively disproportionate extent, are the victims of this inequality. In 2016 a third of the poor were children and in 2017 over 20% of the homeless on any given night were children. And the U.S., Alston reminds us, remains the only nation that has not ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and “ranks 25th out of 29 industrialized nations in investing in early childhood education.”

All this corrodes equality well beyond childhood: “Empirical evidence suggests strong correlations between early childhood poverty and adverse life outcomes….”

Has George Orwell’s message in a bottle washed ashore? So it seems. While his league faltered and ultimately failed, today’s advocates of “equality of chance” – for children as well as for adults – are campaigning for basic income, living wages, and more. All of this, we now know, is very much in Orwell’s spirit. And advocacy of that kind, on the brightly lit stage of the U.N. Human Rights Council, has goaded Trump’s Orwellian administration into yet another flagrant display of hostility to human rights.

Trump’s voice will ultimately fall silent, but Orwell’s voice will echo for centuries. The remaining chapters in this story remain to be written, and his manifesto offers a road map that will long remain pertinent.

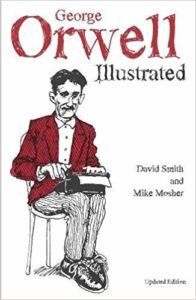

Orwell’s manifesto appears in George Orwell Illustrated (Haymarket Books, 2018), by David Smith with art by Mike Mosher.

David Smith is a professor of sociology at the University of Kansas and Mosher is a professor of art at Saginaw Valley State University.