Here at Kiesha’s Preserve near Paris, Idaho we became aware in 2011 that a 2500-acre mineral lease close to the Preserve was undergoing exploration and permitting in order to mine the phosphate ore. We were greatly concerned that the noise from blasting, mining, stockpiling and hauling of ore would adversely affect wildlife and our wildlife protection and habitat restoration effort. Our investigation of this planned mine revealed many problems and issues, not the least of which were also plans to use the main street through Paris as a route for massive haul trucks to transport ore to the rail siding at Montpelier, about 10 miles away. Based on the ore to be transported, we calculated about 55 haul trucks per hour passing through the town. That’s 110,000 trips per year. This revealed to us the significance of such an operation and we began commenting on State and Federal agency actions for phosphate mining here due to effects on the wildlife corridor we work to restore. We named this corridor the Yellowstone to Uintas Connection and established a non-profit in 2012 with the same name to draw attention to the problems for wildlife that exist here.

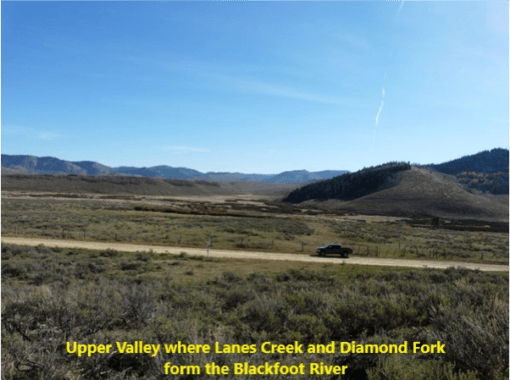

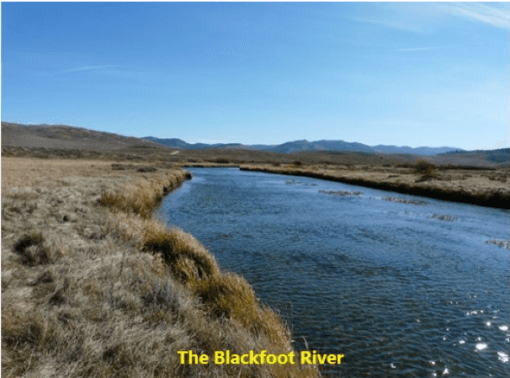

Then, three years ago I visited the Blackfoot River to observe wildlife habitat conditions related to permitting of a phosphate mine, the first of four we have been addressing since. I drove through the Blackfoot River Narrows into Upper Valley where Lanes Creek and Diamond Fork merge to become the Blackfoot River. The mountain ranges fall away to the north towards the Caribou and Snake Ranges and ultimately to Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. To the east lie the Webster, Salt River and Wyoming Ranges. At first glimpse, I thought of Yellowstone and its big valleys, Lamar and Hebgen. I thought of the early explorers like Kit Carson, Donald McKenzie and others who met and traded at rendezvous here in SE Idaho and near Bear Lake in the early 1800s.

As I observed the large strip mines that destroy aspen, conifer and sagebrush habitats, bury watersheds and pollute streams with toxic metals, I thought about what has been lost. Today, cattle and/or sheep in the thousands also graze nearly everywhere, polluting streams, degrading stream habitats and depleting native plant communities. High road densities have turned our Forests into motocross tracks for atvs and dirt bikes and mud bogs for pickups with gutted mufflers. In winter they are replaced with snowmobiles that race around rapping their engines and essentially have no limitations. There is little peace or quiet sanctuary for wildlife or humans.

The Yellowstone to Uintas Connection is a system of higher elevation mountains and valleys that combine into a regionally significant wildlife corridor. This corridor connects the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and northern Rockies to the Uinta Wilderness in Utah and the Southern Rockies. It is a critical part of the Western Wildway, the 6000-mile long wildlife corridor connecting Mexico to Alaska. Historically, Canada lynx, wolverine, grizzly bears and other wide-ranging species traveled this corridor. Since the death of Old Ephraim in 1923, Grizzlies are long gone from the Y2U Connection in Idaho and Utah, while lynx and wolverine rarely pass through. The habitats these animals depend upon have been fragmented to the point of abandonment of the area by these and other keystone species while the land management agencies look on.

My visit to the Blackfoot River revealed what I had thought existed mostly in West Virginia coal mining country. But here it was, strip mining and mountain top removal. I had not made the connection with phosphate mining here in our mountains with the Monsanto (now Bayer), Simplot and other phosphate processing facilities in Soda Springs and Pocatello where phosphoric acid, Roundup herbicide and fertilizers are produced.

Phosphate mining has been occurring here since the early 1900’s but modern technology and earth-moving equipment have allowed it to accelerate the destruction of mountains, watersheds and forests, bury streams with selenium-containing overburden and eliminate natural habitat permanently. Approximately 15% of phosphate ore production in the US occurs here with the rest in the southeastern US.

The mining and processing of phosphate ore has resulted in numerous contaminated sites being investigated under CERCLA (Superfund) for soil, vegetation, ground water and surface water contamination. A Preassessment Screen for the SE Idaho Mine Site (PAS) by the Trustees (US Dept of Agriculture; US Department of Interior; and Shoshone-Bannock Tribes) found selenium contamination at 17 mine sites. Livestock deaths were documented at six of those. Selenium contamination above EPA action levels was found in soils and vegetation. Surface and groundwater are contaminated. For example, the Blackfoot River and its tributaries exceeded the aquatic life standard for selenium with some locations over 1,000 times the standard.

The PAS Screen report notes that response actions were not determined, but “given the geographic extent of the mine site, it is unlikely that remedial actions will sufficiently remedy injury to trust resources.” The State of Idaho Department of Environmental Quality publishes a periodic update giving the status of the actions being taken. The most recent version describes 13 facilities being addressed under CERCLA. All are undergoing Remedial Investigations with two engaged in some cleanup actions. Unfortunately, the nature and extent of contamination is so widespread that remediation will not be complete and “institutional controls”or “monitored natural attenuation”will be used to deny access to land areas or groundwater which will remain polluted for hundreds of years, if not permanently. In the face of this pollution and habitat fragmentation, permitting of new mines rushes forward.

Our analysis and comments on the recent Dairy Syncline Draft Environmental Impact Statement detail the many issues and failures of the land management agencies, the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management to effectively address the pollution, habitat loss and other environmental impacts. Just a few of these include excavating through faults and earthquake risks; ground water modeling parameters that vary over such a wide range that models used to predict plumes of contamination in the regional Wells Aquifer can’t be trusted; disposal of selenium-containing overburden without documentation of the effectiveness of soil covers; claims of revegetation and habitat restoration without presenting evidence of success; claims that lynx, wolverine, deer and elk will move around the periphery of the disturbance using other available habitat while ignoring the degraded integrity of that habitat; Forest Plan objectives not addressed; corridor integrity ignored; road density and human activity effects on wildlife security not addressed; and over a thousand acres of an inventoried roadless area and its habitats dug up into a pit hundreds of feet deep.

Then there are the processing facilities in Soda Springs and Pocatello. Monsanto, now Bayer’s Soda Springs Plant, has been addressing selenium contamination in ground water since the 1980s, but in recent years monitoring has indicated selenium concentrations are not decreasing at the rate expected. The plume of selenium may extend under homes in the north part of Soda Springs. The Kerr-McGee plant at Soda Springs adjacent to the Monsanto operation extracted vanadium from phosphate ore. It was listed as a superfund site in 1995 with a Record of Decision. Deed restrictions were placed on 547 acres of land adjacent to the facility due to site-related contaminants such as arsenic, manganese, molybdenum and vanadium in ground water. In 2009, the company (Tronox, the owner and spin-off from Kerr-McGee) filed for bankruptcy and the site is now managed under an environmental response trust. Itafos (formerly Agrium) processes phosphate ore from its mines into fertilizers at its Soda Springs Conda facility which is also undergoing remedial actions under CERCLA. Recent judgements in lawsuits over Roundup causing cancer have resulted in Bayer being on the hook for huge monetary damages. With thousands of lawsuits left, will Bayer be around to remediate its contamination and restore habitat and watershed damage from mining and processing?

The Simplot and FMC Corporations in Pocatello have historically processed phosphate ore into fertilizers and elemental phosphorous for use in a variety of products such as cleaning compounds. Their operations resulted in a superfund site known as Michaud Flats that covers 2,530 acres. Lands affected include the Shoshone-Bannock Fort Hall Reservation, portions of Power and Bannock Counties and the Cites of Pocatello and Chubbuck. These sites were addressed in a 1998 Record of Decision by EPA to provide remedies. Today, these remedies include capping contaminated soils, containment of contaminated groundwater, monitoring and institutional controls. Institutional controls prevent future development for residential use. Groundwater flowing beneath the facilities discharges to the Portneuf River. Ore from the mines is shipped via rail to FMC and by slurry pipeline to Simplot from processing facilities located at the mines. Arsenic, lead, cadmium, mercury, selenium and other contaminants have been documented at the sites.

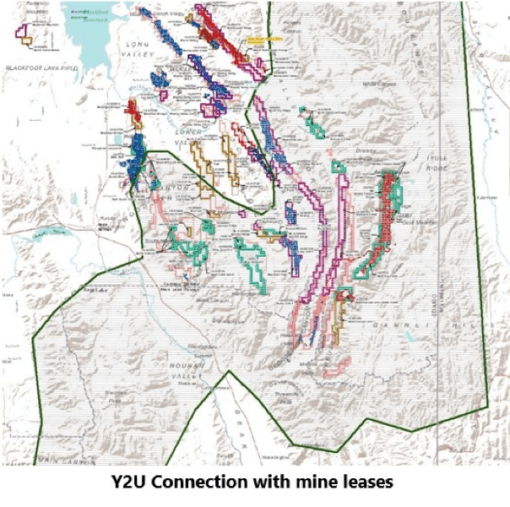

We have mapped the mine leases showing the more than 30,000 acres present in the Y2U Connection. If an animal travels around one mine, it encounters another. Then there are the roads we mapped using the Forest Service data for open roads. When we mapped the Huckleberry Basin Inventoried Roadless Area, a portion of which is to be mined, there are no wildlife security areas remaining if noise is addressed.

The mine footprints can be thousands of acres plus haul roads, overburden disposal areas, electric transmission lines, slurry pipelines and tailings ponds. For example, Simplot’s Dairy Syncline tailings pond is 9,777′ long, 3,586′ wide and 140′ high at the dam. Given the recent Vale tailings pond failure in Brazil, why this risk?

The Bureau of Land Management is proposing to sell the land for the tailings pond to Simplot because, “the BLM does not believe managing a tailings pond on public land is in the public interest because it does not want to be responsible for long-term management of the tailings pond, nor does it want to incur the potential recreation liability of the facility…”.

While the DEIS mentioned this is a seismically active region, it failed to describe the role of mining in creating seismic activity. The Quake Bulletin data for this area documented 1625 earthquakes since 1960. The Dairy Syncline mine DEIS indicates blasting will occur 400 times per week in this heavily faulted zone. Over a 30-year mine life, the number of detonations would be approximately 624,000 blasts in drill holes in the bedrock. What are the consequences of this on seismicity? The tailings pond and dam? We will eventually find out as this experiment by mining companies and our public trust agencies, BLM and the Forest Service continues.

A quick web search indicates that mining can reactivate existing faults. A National Geographic Article cites a study of 730 sites where human activity caused earthquakes over the past 150 years. “According to the report’s data, found on a publicly accessible database, mining accounted for the highest number of human-induced earthquakes worldwide (many earthquakes clustered around 271 sites). The removal of material from the earth can cause instability, leading to sudden collapses that trigger earthquakes.”

The Wise Uranium Project provides a summary of major tailings dam failures including the recent failure of the Vale facility in Brazil that released 12,000,000 cubic meters of tailings that traveled 7 km down the watershed into the Rio Paraopeba and killed hundreds of people. The Wise Uranium Project shows numerous tailings dam failures, including for phosphate mining projects.

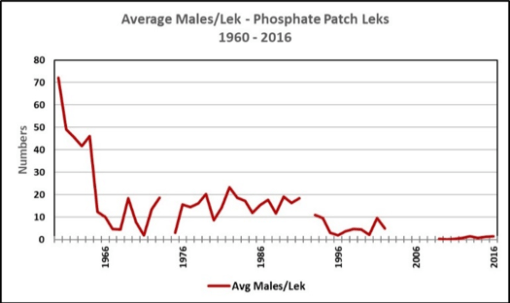

What is the ultimate cost of this contamination? We have no idea of the ultimate burden nature and the public will have to bear as pollution lasts for centuries, companies come and go, or go bankrupt as in the case of Tronox. But these are the costs related to chemical contamination. There are many other costs including the loss of tens of thousands of acres of habitat, including aspen, conifer, sagebrush, streams, springs, wetlands, watersheds, native soils and plant communities. The carbon stored in vegetation is lost as is much of the carbon stored in topsoil as it is dug up, hauled, stockpiled, loaded, hauled again and mixed with lower organic content soil from deeper layers for covering overburden. Wildlife habitat such as deer and elk summer and winter range is lost. Sage and sharp-tail grouse, migratory birds, owls, raptors, small mammals, reptiles and amphibian habitat is lost. Recent land use plans have based their determination of Priority, Important or General sage-grouse habitat based on populations already driven to near extinction, so today designated sage-grouse habitat is minimal in extent and considered “marginal”. Leks that once had large numbers of sage-grouse attending, now have none. As mining and other extractive uses have progressed unabated, populations have declined and been eliminated.

Then there is the native Yellowstone cutthroat trout that appears to be on its way out of the area streams due to sediment, nutrient, habitat loss and selenium pollution along with dewatering for livestock water and irrigation for livestock pastures. Livestock trample and graze stream banks, removing bank protecting vegetation, including willows, resulting in accelerated erosion. Livestock defecating in or adjacent to the streams increase E. coli and nutrients. When we have raised the problem of livestock pollution and stream damage, Idaho DEQ has responded by saying compliance with water quality criteria is voluntary.

Reclamation consists of planting a seed mix on the soil cover placed on overburden piles that refill the mined-out pits or cover external overburden piles. One such overburden disposal area at Simplot’s Smoky Canyon mine buried Pole Canyon Creek and resulted in creation of a Superfund site from selenium contamination. Mitigation credit is taken for this reclamation, but we see no data and analysis comparing these reseeded areas to what was lost or proving the cover prevents leaching of toxic chemicals. Clearly at Smoky it did not. Can an aspen or conifer forest be replaced with a seed mix of herbaceous plants on a modified soil cover with unknown outcomes?

Mines also alter the watersheds. In the case of the Dairy Syncline mine, 5,200 acres will be removed from the Slug Creek watershed, a stream already impaired by sediment, selenium and reduced flow. Simplot claims in its DEIS that the impact to flow in Slug Creek would be “minor, local and short term”. In the past two surveys of Slug Creek nearly ten years ago now, only two Yellowstone cutthroat trout were found.

What about the lost habitat? There is no replacing what is lost under the current scenario. What is done instead is based on what is called a Habitat Equivalency Assessment in which the lost habitat is given a dollar value. This value is discounted over time as the mining phases progress and the habitat is lost sequentially. Credit is given for reclaimed areas planted with herbaceous plants as mining proceeds. This provides a dollar value that is then paid to a third-party land trust for unspecified mitigation. We could find no dollar amount for the Dairy Syncline or other recent mines being permitted, but in 2016, the Rasmussen Mine expansion by Itafos committed $1.2 million to a local land trust for this mitigation.

“Compensatory mitigation for losses of Aquatic Resources” may also be paid to the US Army Corps of Engineers to replace wetland lost functions and values. How does a check replace a stream? Simplot has, identified a potential wetland mitigation site on their private property, likely to be grazed by livestock, so we are unsure about its ability to provide wetland and wildlife functions. It is also unclear whether they will be paid or if mitigation for all ecological values lost will consist of merely writing a check to land trusts, the Army Corps of Engineers or Simplot itself. Let’s place this in perspective with potential revenues for this single mine.

The agencies and Simplot failed to furnish revenue estimates for the Dairy Syncline mine while the counties claimed confidentiality and did not provide natural resource related financial figures. This precludes an accurate analysis. So, we must approximate. Using our own estimate of the economically recoverable ore based on a USGS study, we calculated annual revenue for the Dairy Syncline mine of about $543 million per year. The mine life is projected to be 30 years. This would sum to $16.3 billion in revenue for Simplot. How does this compare to these one-time payments for upland and wetland habitat values? Even a $10 million one-time payment would be insignificant at 1.8% of one-year revenues or .06% for the life of the mine. We would be interested to see the real figures for revenue and mitigation by the mining interests. Or for that matter, a report on the prior mitigation projects with monitoring data demonstrating the outcomes and comparing them to what was lost.

How would one value the wildlife and natural values lost? The US Fish and Wildlife Service has periodically produced an analysis of fishing, hunting and wildlife watching recreation statistics, including expenditures. The 2016 analysis indicates annual national expenditures are $75.9 billion for wildlife watching, $46.1 billion for fishing and $26.2 billion for hunting. Idaho figures from the 2001 edition totaled $767 million, almost 20 years ago and likely an underestimate. Perhaps the Caribou Targhee National Forest should consider the millions of visitors to Yellowstone National Park to view wolves, bears and other wildlife and what those economic benefits are compared to the loss of these high value species in its Forest on behalf of extractive uses such as mining, noise and habitat fragmentation by roads and trails for off-road vehicles. Off-road vehicles are not present in YNP in summer but still millions of people visit. Make the connection.

The mitigation provided by the mining interests does not place a value on most lost ecosystem services, including watersheds or water supplies, contaminated streams and ground water, losses in beauty and natural values that also provide ecosystem services, cultural benefits for Tribes, and long term permanently sustainable economic values. There are mechanisms for evaluating ecosystem services in numerous studies such as those published by Dr. John Loomis of Colorado State University. These ecosystem services have many attributes that are lost over the long term such as behest and intrinsic values. Loomis and others provide means of determining market values for these services.

Lynx, wolverine, grizzly bears, bighorn sheep, sage grouse, native fish, migrant birds, raptors, amphibians and other wildlife can’t speak or defend themselves from this onslaught. They need our help.