Photograph Source: Derek Redmond and Paul Campbell – CC BY-SA 3.0

The Woodstock music festival, now a legendary event, took place a long time ago and memories have largely faded. Folksinger Joan Baez can’t really be faulted for saying recently that at Woodstock, “Nobody was really thinking about the serious issues.” True, not many, but not nobody, either. Baez also suggested in a recent interview with the New York Times that she was the only one at Woodstock who was concerned about the war, civil rights and social change. Her husband, David Harris — who had been arrested and convicted of draft evasion (a felony)— was serving a 15-month sentence in a federal prison. At Woodstock, Baez sang her heart out. No teenybopper or hippie chick, she was a professional musician. She was also pregnant and she had a driving mission to bring peace and love to the world.

Still, Baez wasn‘t the only person at Woodstock who wanted to transform the world and to transform it as soon as possible. In his own idiosyncratic way, Abbie Hoffman was no less committed to a revolution than Baez, who offered her own definition of revolution to the Times. “A revolution,” she said, “involves taking risks and going to jail and all that stuff that happened in the civil rights movement and the draft resistance.” Abbie went to Mississippi in 1965. He opposed the War in Vietnam for years.

By the summer of 1969, when he almost 33, he had taken big risks in the civil rights and the anti-war movements and paid for them by going to jail. Mid-way through his book, Woodstock Nation: A Talk-Rock Album, which he wrote in a few weeks, he lists ten of his most recent arrests. They include: one on the campus of Columbia University in New York in 1968 during the student strike; another in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention and the “police riot” for having the  word “Fuck” on his forehead; and yet another the same year, at the hearings of the House Committee on Un-American Activities in Washington D.C., where he wore an “American flag shirt.”

word “Fuck” on his forehead; and yet another the same year, at the hearings of the House Committee on Un-American Activities in Washington D.C., where he wore an “American flag shirt.”

A battle-scared Hoffman went to Woodstock to politicize it. Specifically, he wanted to alert the crowd to the imprisonment, for the possession of two joints, of John Sinclair, the founder of the White Panther Party.

The Yippie demands for a “Free Society,” which are reproduced in Woodstock Nation, offers eight items. The first is “Free John Sinclair and all other political prisoners.” Item seven, which is addressed to the powers-that-be, states “You will convince the Culture-Vultures who have taken our culture…and turned it into profits to pay $300,000,00 in reparations.”

On the second day of the festival, August 16, 1969, Hoffman leapt to the stage when Pete Townshend and the Who were performing. He grabbed the mic and shouted, “Free John Sin…” That was as far as he got. Townshend clonked him on the head with his electric guitar and shouted, “Get the fuck outta here.” Hoffman replied “You fascist pig.”

Fascism is an undercurrent that runs all the way through Woodstock Nation. Hoffman calls Ronald Reagan “the fascist gun in the West.” He adds that, “We always knew that Hitler was running the State Department, now it seems he has taken over the Justice Department as well.” Hoffman thought that the Woodstock mix of rock ‘n’ roll, marijuana and sex was compatible with an American version of fascism.

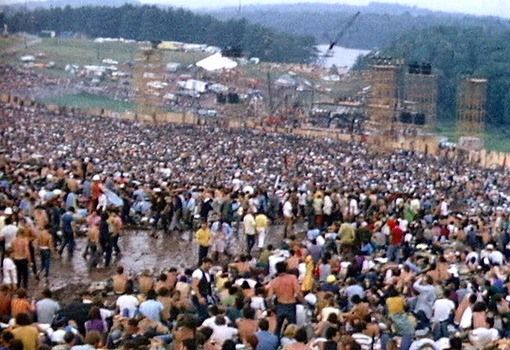

In the chapter titled “Power to the Woodstock Nation,” he asked a series of crucial questions about the crowd of 400,000 people. “Were we pilgrims or lemmings? Was this the beginning of a new civilization or the symptoms of a dying one? Were we establishing a liberated zone or entering a detention camp?”

Hoffman didn’t answer the questions with a yes or a no, though he reminded readers that, “When the Jews entered the ovens at Dachau, the Nazis played Wagner music, passed out flowers and handed out free bars of soap.” The flower children might be, he reasoned, sacrificed to the god of war. In fact, as he recognized, young men were sacrificed to the god of war on the battlefields of Vietnam.

By the time he wrote, Woodstock Nation, Hoffman was already an iconic and infamous figure. His account of the music festival, which might have been called “Fear and Loathing at Woodstock,” made him even more iconic and infamous than he had been before Woodstock. Ever since 1969 when Random House published his book, Hoffman has been linked to the Woodstock festival and to the phrase “Woodstock Nation,” which he coined. He borrowed his concept of a nation of hippies from the Black nationalists of the 1960s. Having read Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael and James Foreman, he knew how powerful an idea nationalism could be.

The phrase “Woodstock Nation” has been borrowed and recycled again and again over the past 50 years, and used as the title for dozens of books and articles. It’s part of Hoffman’s enduring legacy, and a key part of his contribution to the cultural revolution of the Sixties. No one, or at least very few people who were alive then and over the age of 20, have forgotten the phrase, though no one seems to have reread Woodstock Nation carefully.

New York Times music critic John Pareles wrote recently that “Woodstock simply identified a big, promising segment of the youth market, ready for the commercial exploitation that would ensue almost immediately.” Pareles added, “Woodstock Nation, despite Abbie Hoffman’s hopes when he coined the term, turned out to be a demographic rather than a political force.”

Sorry Pareles. A close reading of Woodstock Nation shows that Hoffman was well aware of the fact that the “culture vultures,” as he called them, in the corporate world were already exploiting the youth market and making a tidy profit.

Almost everywhere he looked in 1969, Hoffman saw the “rip-off’ of hippie culture and African-American culture, too. That’s why he demanded reparations. He also recognized that capitalism incorporated the very language of the Left. The word “revolution,” which had negative connotations in the U.S. for decades, suddenly was associated with all things good. At the start of his first book, Revolution for the Hell of It, he offered a quote from a TV commercial: “Dash: A Revolution in cleansing powder.” Before long, the mass media would talk about “the Reagan Revolution.”

Woodstock Nation offers valuable insights into Hoffman’s own life. Not surprisingly, the author calls himself a “self-destructive, egotistical, horny, show-off, paranoid-schizophrenic.” And that’s not all. He also describes himself as “white,” “male” and a “schmuck.” No wonder biographers have had a difficult time wrapping their heads around Hoffman and the late 1960s which he describes as “an awkward time of anxieties and doubts.”

There’s warmth in Woodstock Nation, especially in the heart-felt, albeit brief, tributes to Joan Baez and Pete Seeger. There’s also an un-romanticized view of Woodstock as an expression of “functional anarchy” and “primitive tribalism.” Hoffman had a sharp eye. He noticed that Baez was pregnant and that when it rained, Wavy Gravy and the members of the Hog Farm went on feeding people.

One of the pleasures of reading Woodstock Nation today is Hoffman’s experiment in storytelling. He included a letter to John Mitchell in the Department of Justice, a letter that he imagines Che wrote right before his death, and an interview in which he asks the questions and provides the answers. As an “album,” the book goes around and around in circles and not in a linear way.

Woodstock Nation effectively conjures a distant time and place, but it isn’t merely an artifact from another era. Hoffman asks the big questions that ought to be asked now by activists and promoters of new technologies and alternative life styles.

“Is this the beginning of a new civilization or the symptoms of a dying one?” That question is as valid today as it was in 1969. It’s valid even though Hoffman himself could be an obnoxious sexist. In Woodstock Nation, he proclaims, “God, I’d like to fuck Janis Joplin.”

Hoffman also touts John Sinclair as a “mountain of a man” who can “fuck twenty times a day.” His sexism notwithstanding, he paints a complex portrait of the contradictions in the counterculture of the Sixties, and the exploitative role of corporate capitalism. He reveals his own flaws, too, and a sense of self-righteousness, which he shared with Baez. Too bad they didn’t team up. After all, at Woodstock they were political activists in a sea of largely apolitical hippies. A Hoffman-Baez alliance was not meant to be. They were as different from one another as Baez was from Janis Joplin who held up a bottle of alcohol in a paper bag when Baez invited her for tea.