South Africa is one of the most difficult places to combat fossil fuels, including the petrochemical complexes that regularly poison the third largest city, Durban, founded by white settlers on the east coast in the mid-19th century. The average South African emits 9 tons of CO2 annually, which is the 11th highest among countries with at least 10 million residents. And measured in CO2/capita/GDP – in order to assess an economy’s carbon intensity – it the world’s third highest level, behind only Kazakhstan and the Czech Republic.

There is no average, though, because the racial Apartheid system that ended in 1994, at least politically, and the ‘class Apartheid’ processes that took its place, meant that wealthy white males still retain enormous power and wealth, and they vastly over-pollute. Two thirds of the country’s citizens – mostly blacks and women – live in poverty, below the official line of $3.30/day. With the rise in electricity prices, their power supplies are increasingly, dangerously dirty: wood, coal or paraffin for heating, lamps and stoves. They have ‘energy-switched’ backwards in time, unable to pay the parastatal Eskom’s retail electricity bills. The price of a kiloWatt hour quadrupled in price over the last decade due to a decision to build the world’s two largest coal-fired generators now under construction. Corruption, delays and the incompetent boiler manufacturer Hitachi doubled the construction costs of the two 4800 MegaWatt plants from $8 billion each when financing was arranged in 2010 (primarily by the World Bank, in its largest ever loan) to $15 billion each today.

Can these contradiction-riddled conditions at the national scale give rise to a deeper Climate Justice (‘CJ’) movement, drawing on local strengths, and adding the renewed power of the youth? This is the question posed by many of the country’s environmental-justice and eco-socialist strategists, after a quarter-century of political liberation. But freedom has been profoundly distorted by neoliberal-nationalist ideology and crony-capitalist practices, including periodic repression of socio-economic rebellions. In the process, environmental justice has been side-lined.

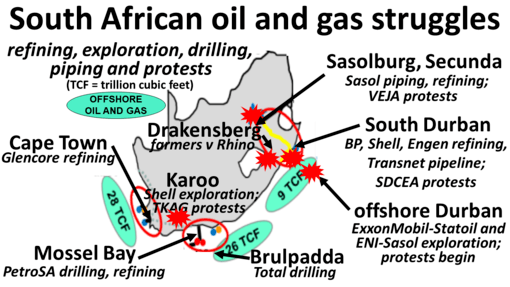

Locally, fossil fuels are facing opposition. A petrochemical complex regularly poisons the third largest city, Durban, founded by white settlers on the east coast in the mid-19th century. There, Africa’s largest oil refinery comes under repeated attack for both local and global pollution by the South Durban Community Environmental Alliance (SDCEA). The quarter-century battle heated up in 2019 because, 1200 km down the Indian Ocean cost, 45 billion cubic meters (300 million barrels worth) of new offshore oil and gas condensate were discovered by Total. Announced by excitable politicians with great fanfare, doubts have subsequently developed about the extremely difficult conditions for extraction.

In the other direction, 2800km up the coast at Rovuma in northern Mozambique, are even greater quantities of gas ($20 billion worth is thrown around), some of which Total is buying from Anardarko, with ExxonMobil and Eni hot on its heels. Older gas fields at Pande and Temane, in the middle of the country, are being drained by Sasol, of which 20% creates energy for local consumption and 80% is pumped 900km to South Africa’s main inland refinery in Secunda. There, drips of liquid petroleum are squeezed with such an intense application of energy that this small city of 40,000 is the world’s single largest CO2 emissions point source. Local activists fighting hard here are led by the Vaal Environmental Justice Alliance.

In between, in Durban, oil companies are swarming 3kms offshore with exploratory drills nearly 4km deep in the Agulhas Current, the second most turbulent ocean waterway, after the Gulf Coast. But notwithstanding all the anti-oil activism – divestment, ‘unburnable carbon’ and ‘stranded asset’ pressures, as well as direct-action protests – against the oil majors, four of them anticipate billions of dollars in profits once they set up rigs: ExxonMobil, Statoil, Eni and Sasol, respectively the biggest from the U.S., Norway, Italy and South Africa.

Durban is already the regional oil hub for refiners Shell and BP, alongside Malaysian-owned Engen. Nearby, within Africa’s largest container harbour, are more massive oil storage facilities. On South Africa’s cold Atlantic coast at Saldanha, Saudi Arabia’s Aramco is also considering a major investment in oil storage. And two hours north of Durban at Richards Bay – home to one of world’s largest coal export terminals – the parastatal port manager, Transnet, aims to set up an LPG terminal. In all this seaside ecological risk-taking, the corporations are being encouraged by government’s ‘Blue Economy’ propaganda.

SDCEA, the country’s leading anti-oil campaigning force, regularly links local health and ecological damage to climate change, and opposes ocean degradation on behalf of local residents, thousands of fisherfolk, coastal small farms and even surfers. Victories have included lowering refinery sulphur emissions and delaying the nearby port-petrochemical complex’s $25 billion expansion. The asthma rate in the Settlers Primary School, between the two mega-refineries, had peaked at 52% of children in attendance in 2004, but is now substantially lower. But the group hasn’t yet shut down the refineries – SDCDEA’s objective – or even lowered their 350,000 barrels/day capacity. And while SDCEA insists that no more offshore oil and gas exploration occur, it is – and most dangerously, the parastatal firm Transnet doubled the size of an oil pipeline from Durban to the main consumption site, Johannesburg, in a controversial $1.8 billion project from 2005-18.

Joining SDCEA, which is based in Durban’s black communities of Wentworth, Merebank, Clairwood and Umlazi (and to some extent also the Bluff, a formerly white residential area), are conservationists from Oceans Not Oil and Wild Oceans. But SDCEA has taken the lead, alongside its groundWork NGO allies, in working against offshore oil and gas, up and down the coastline from Mozambique to Cape Town. Inland, there is also courtroom guerrilla warfare by farmers and environmentalists to counteract threats by the U.S. firm Rhino to frack in the beautiful Drakensburg mountain range and nearby KwaZulu-Natal farmland. In the semi-desert Karoo, Shell’s fracking division is retreating after a courtroom setback. Nevertheless, still lacking climate consciousness, the government’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research is planning a massive gas pipeline across the country.

‘Coalanization’ continues

Coal mines supply 90% of Eskom’s generation inputs, as well as around 80 million tons of exports. The main battles against coal occur because of its local damage to public health, water, land and air. On grounds of climate change, war is being consistently waged by three forces: NGOs, lawyers and communities in destructive coal zones. Unfortunately organized labor is basically pro-coal, though that could change.

In general, local activists are not yet as militant and effective as, for example, Germany’s Ende Gelände annual movement, in part because the society is still poorly organized for understanding and acting on climate politics. So progress currently relies upon pressure against financiers, legal strategies on difficult terrain, and mainly localistic protests. Some community disruptions occur in the immediate vicinity of coal mines and coal-fired power plants, such as road blockages, while others are using the courts to prevent two privatized coal-fired plants from being built, so far successfully.

Fragmentation has prevented the emergence of a general movement against coal, and indeed against climate change. Some NGOs with specific agendas are internationally affiliated. Greenpeace Africa, for example, issues important research against the coal industry’s air and water pollution, and periodically engages in direct actions against the main electricity company and state officials, although these are mostly small-scale and symbolic. The South Africa branch of 350.org specifically targets coal industry financiers – successful against several local banks – and is central to the broader “decoalonize Africa” campaign. (Its main success was claimed this year in Lamu, Kenya – against a Chinese project with anticipated South African coal imports until Kenyan mines are developed). Unfortunately the CJ angle is quite weakly articulated by these NGOs, whether because they are so single-issue in nature or simply not yet sufficiently sensitive to race, class, gender, generational and other inequities.

Those with a forthright CJ orientation include local NGOs who have their own community-based partners. The most prominent is “Life after Coal,” consisting of the hard-working groups Earthlife Africa and groundWork, and progressive lawyers at the Centre for Environmental Rights (CER). Sometimes they attempt creative objections to Environmental Impact Assessments on grounds that climate change is not properly incorporated into planning, and they harass state agencies for disclosure and stronger enforcement of environmental regulations. Sometimes their partners are involved in mass-based protest, although the last substantial one – with at least 10,000 marching – was in late 2011 when Durban hosted the UN annual climate summit. The counter-summit was messy, as it revealed persistent splits between the two philosophies: CJ (led at the time by the Democratic Left Front, which is now dormant) and Climate Action (mainstream NGOs such as WWF).

Today, the most militant network of grassroots anti-coal activists is Mining Affected Communities United in Action. Others include the Mining and Environmental Justice Community Network of South Africa and Women from Mining Affected Communities United in Action. In the coal-rich Mpumalanga province, especially around the most affected two towns, Emalahleni (Witbank) and Carolina, these groups and the Southern African Green Revolutionary Council have an important impact, both in organizing and motivating an eco-socialist ideology. However, no major victories can yet be claimed, aside from Earthlife and CER using an Environmental Impact Assessment to slow construction of new privatized coal-fired power plants.

The highest-profile battle against coal is being waged on the border of Africa’s oldest wildlife reserve, Hluhluwe-iMfolozi, famed for conservationist Ian Player’s breeding of white rhinos when they were on the verge of extinction a half-century ago. At the park’s southeastern entrance are two neighbouring villages: Somkhele – where activists have attempted to close down one fast-growing coal mine – and Fuleni, where they have so far prevented another from opening. Within Somkhele, the Johannesburg-based Tendele mining house and local elites are opposed by the Mfolozi Community Environmental Justice Organization, backed by ecologists in Player’s tradition, especially attorney Kirsten Youens and the Global Environmental Trust. The latter group explains, “For seven years, the mine operated without a valid water use license. The mine also exhumed and relocated hundreds of graves without necessary permits and reneged on its agreed compensation to families for the exhumation of the remains of their ancestors – a very serious matter in Zulu culture. The mine has taken the property of hundreds of people without compensating them for their land, only for their homes.”

But tensions have risen between Somkhele men expressing a desperate need for work – even in the hazardous coal mine – on the one hand, and women articulating their self-preservation of homes, clean air, water access, small farms and livelihoods on the other. Mineworkers and ethnic leaders in league with the coal company won the latest round – a dispute over expanding the existing Somkhele mine – in an August 2018 court battle, but the case is on appeal. It illustrates the desperate need for a Just Transition strategy and sufficient funding for alternative employment of an ecologically constructive, meaningful character, instead of coal mining.

Scenes from Somkhele mine, Fuleni resistance and a 2018 showdown at court

Source: Global Environmental Trust (Rob Symons)

In Johannesburg, the Somkhele and Fuleni activists have another vital ally: the eco-feminist fusion of continent-wide women farmers, environmentalists and sophisticated NGO critics in the group African Women Unite against Destructive Extraction, better known as WoMin. They are the most explicit in fighting coal using climate change narratives.

Movements like these fighting against coal are sometimes working at cross-purposes with a different set of NGOs whose aim is to merely ameliorate local damage from mining, and who rarely if ever consider climate change or the massive economic loss caused by non-renewable resource depletion. Such arguments are ‘outside box’ for reformist NGOs insofar as acknowledging their logic would justify leaving minerals, oil and gas underground. Their annual Cape Town meeting occurs at the same time the mining industry gathers for their ‘Mining Indaba’ (the latter word meaning consultation) and is known as the Alternative Mining Indaba.

Since the NGO-driven event generally fails to ‘connect the dots’ between micro-mining grievances and bigger-picture problems like climate, energy choices and general resource looting, critics organized the November 2018 Thematic Social Forum on Mining and Extractivism in Johannesburg. It offered a much more critical perspective, demanding “the right to say no!” to corporate land and mineral grabs. CJ was a consistent theme there, too.

Two cyclones and a rain bomb

In mid-2019, the contradictions and limits of all these approaches came into focus when hundreds of regional activists in the Southern African People’s Solidarity Network held their annual meeting at the national museum in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Rural Women’s Assembly members who offered testimonials from cyclone-affected sites in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Malawi and South Africa. It was their mutual aid against flooding, during the terrifying weeks of March-April 2019, that allowed survival in the face of an unprecedented double-whammy of cyclones.

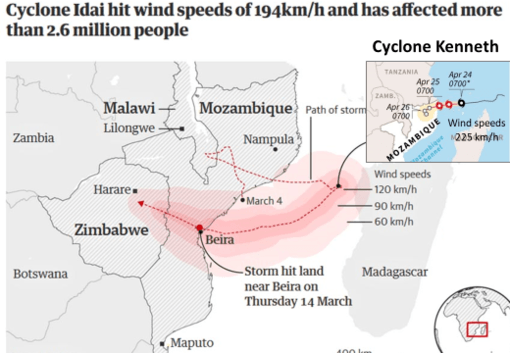

Idai and Kenneth were the worst cyclones on record in this region, and in between was a ‘Rain Bomb’ on Easter Monday that devastated South Durban and areas further down the coast. Scientists agree that these storms were more vicious due to climate change, for the temperature of the Indian Ocean offshore Beira, Mozambique was recently higher than normal by more than 2 degrees, the impact of which was to make Idai much more intense. With sustained winds of 195 kph at peak, Idai was the Southern Hemisphere’s third most destructive storm in recorded history (following cyclones in Madagascar in 1892 and Indonesia in 1973).

Governments estimated Idai’s fatalities at 1,078: 602 Mozambicans, 415 Zimbabweans, and 60 Malawians, with more than two million people suffering other loss and damage, and sustained threats of cholera. Two thirds of Mozambique’s and Zimbabwe’s staple maize crop was destroyed, not only by the flooding but also drought that hit elsewhere.

Zimbabwe’s low rainfall is unprecedented. The country’s main power source, the Zambezi River, dropped sufficiently low as to extinguish hydropower supply at the Kariba Dam, the world’s largest artificial lake. The Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery confirms, “Mozambique ranks third among African countries most exposed to multiple weather-related hazards and suffers from periodic cyclones, droughts, floods, and related epidemics.”

The links between Cyclone Idai and climate change were acknowledged here by those with a social conscience. The South African government mainly sent their armed forces and technicians to help rebuild pylons to restore the main electricity supply from Mozambique, from the Cahorra Bassa mega-dam on the Zambezi River. South Africa suffered a major set of blackouts the week Idai hit, due to the disruption of more than 1 MW supply. The main agency assisting Mozambicans was a famous South African charity, Gift of the Givers, which provides relief support across the world.

Five weeks later, on April 22, 170 mm of rain fell on Durban and its southern hinterlands, leaving 71 dead. The prior record was October 2017 when only 108 mm fell in a day. And the following week, Cyclone Kenneth hit Mozambique – near the newly-discovered northern oil and gas fields – at the scarcely-populated border with Tanzania, so although winds reached 225 km/hour, there were only a few deaths.

The cyclones and rain bomb revealed the region’s terrible vulnerabilities, as did the 2019 drought in South Africa’s, Mozambique’s and Zimbabwe’s main food producing areas and the Cape Town water shortage that from 2015-18 left the city’s residential taps nearly bone dry. As Mozambique began to recover, the most popular television talkshow – the SA Broadcasting Corporation’s Big Debate – made Cyclone Idai a central point in a furious two-hour dispute over how to link the energy and climate crises, and solve both.

What is also much clearer after the 2019 extreme weather, is South Africa’s ‘subimperial’ role in the region, including as a central force behind environmental damage. It is increasingly important – and easy – to show that the wealthiest South Africans have a ‘climate debt’ liability for this damage. Fewer than three dozen corporations operating in South Africa – led by BHP Billiton, Sasol, Glencore, Anglo American, Arcelor Mittal and other smelting and mining houses in the Energy Intensive Users Group – are responsible for 40% of the electricity consumption. In general, as University of Manchester climate scientist Kevin Anderson points out, “Almost 50% of global carbon emissions arise from the activities of around 10% of the global population,” an indicator of how extreme climate injustice has become.

Climate Justice requires that not only the historically highest emitters internationally, but also South African ‘Global North’ residents and corporations, start to acknowledge guilt, and identify ways to both pay reparations for damage, according to standard polluter-pays principles, and forthwith reduce emissions with a clear phase-out strategy.

This point was made after Cyclone Idai by the Rural Women’s Assembly: “The three countries now affected by this unfolding disaster – Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Malawi – have among the world’s lowest emissions rates. We demand that rich countries who continue to pollute the Earth’s atmosphere with greenhouse gas emissions commit to pay compensation for the damage and loss of life resulting from this latest storm.”

As expressed by Anabela Lemos, director of Justiça Ambiental! (Friends of the Earth Moçambique), “People in Mozambique know this is climate chaos. They know what’s going on. They are going to come and challenge everyone in northern countries and ask: why are you continuing to do this to us? Stop this genocide.”

The Harare-based Centre for Natural Resource Governance in Harare released a statement specifying how reparations could be made:

the rich countries must pay their climate debt to the Zimbabwean people – but the Zanu PF government and Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube cannot be trusted to manage the payments. Instead, we need trusted agencies in civil society to receive aid and direct transfers to the ordinary people affected. This could be done simply by arranging payout systems in the affected parts of Zimbabwe, so that everyone living in those areas would get a reparations payment. There is need to compensate families for loss of lives, destruction of homes and even loss of food, livestock and domestic utensils. The situation is dire in fragile states where governments have misplaced priorities – which relegates human security to humanitarian work of NGOs and well-wishers.

This doesn’t yet change everything – but could and should

Even though these extreme incidents of climate damage are becoming more obvious, the construction of a South African CJ movement has been elusive. One reason is the philosophical differences between the environmental justice and conservation movements. Occasionally these movements come together in specific sites of unity, such as defending against coal mining on the border of the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi reserve (where the white rhino was saved from extinction).

But there are several missing links before they can generate a national movement with equivalent weight to, say, the Treatment Action Campaign which demanded that generic AIDS medicines be universally available. Their victory raised life expectancy from 52 to 64 years from 2005-15, by getting life-saving drugs to five million South Africans who previously could not afford them.

One gap in climate activism is the failure to reframe climate change the way Naomi Klein did in 2014: This Changes Everything. That would entail conjoining all manner of struggles over energy, transport, agricultural, production, suburbanization and waste disposal processes that cause climate change – each step of the way, insisting on ‘Just Transition’ policies and projects that switch workers from dirty to clean jobs with no loss of pay, and with sensitivity to geographical impact.

The climate movement would then need more unity of purpose in everything from popular education, to militant activism, to media advocacy, to watchdogging the national policy process to lobbying legislatures, to filing regulatory objections – since Pretoria’s environment and mining ministries generally behave as if they were in the pockets of the polluters – to building up climate-conscious case law in the courts. It would require more support from the various foundations and funding organizations that currently amplify infighting, turf wars and ‘silo’ politics. Also required is stronger youth leadership, where signs include several local manifestations of the Climate Strike: strongest in Cape Town and Johannesburg, but with potential to spread across the country and continent. One promising network was the South African Youth Climate Change Coalition.

Strategically-minded intellectuals were occasionally involved in CJ activism, particularly the group of eco-socialists assembled by University of the Witwatersrand political economist Vishwas Satgar to develop a book-length Climate Crisis critique. Satgar also helped mobilize the South African Food Sovereignty Campaign which in 2018 established a People’s Climate Justice Charter. A team at the Alternative Information and Development Centre put together a 2017 Million Climate Jobs booklet and campaign to support decarbonization, including in the coal fields. Some of the best anti-coal research comes from groundwork. Investigative journalists with a climate focus can be read regularly at Daily Maverick (led by Kevin Bloom) and the Mail & Guardian (especially Sipho Kings).

South Africa’s CJ ideas are recognized as being very different than the Climate Action approach, thanks to 1990s traditions of environmental justice and the 2004 founding of the (international) Durban Group for Climate Justice. However, South Africa remains the world’s most unequal society and cultures of activism differ dramatically from the components that would need to fuse for a proper national CJ movement to emerge: environmental justice advocates (including in the conscientized middle-class), low-income communities, women, labor and especially the youth.

In contrast, the top-down SA Climate Action Network has many more resources and insider credibility with the state and capital, but has a much lower-profile presence in the vital concrete struggles – and too often, insiderism means endorsing weak climate policies such as the UNFCCC, or South Africa’s Integrated Resource Plan for energy and Long-Term Mitigation Scenarios for decarbonization. Very few groups bridge this gap.

Red and green fragments, not fusions – but in future?

As a final and perhaps most important consideration, South Africa also reveals age-old conflicts between environmentalists and organized labor over employment. Often insensitively, Greenpeace fought periodically with two of the largest trade unions, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) and National Union of Mineworkers, whose members include workers in carbon-intensive sectors. Their struggles for better wages in the electricity plants, auto factories, mines, smelters and other heavy industries were openly waged since unions re-emerged during the 1970s, and their strength of purpose was vital to ending apartheid. But they remained opposed to the loss of 100,000 jobs in the main coal district, Mpumalanga, because the government never provided details on what it meant by the oft-repeated mantra, a Just Transition.

Numsa’s staff were once visionary advocates of renewable energy democracy, and by the early 2010s, the union had developed one of the world’s most ambitious Just Transition statements. But Numsa then turned in 2017-19 to fighting against Climate-Action environmentalists over the 10,000 MW of privatized solar and wind projects being installed mainly by European corporations.

As the union’s deputy leader Karl Cloete explained, “the mandate of Renewable Energy projects must be to achieve service provision, meet universal needs, decommodify energy and provide an equitable dividend to communities and workers directly involved in production and consumption of energy.”

The president of the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, Joseph Mathunjwa, agreed that the privatized model should be discarded: “If we leave it to the market, we will not get to the roots of the climate and environmental crisis and workers will be discarded in the existing mining and energy sectors.”

The 800,000-strong SA Federation of Trade Unions held a mid-2018 Working Class Summit with similar rhetoric: “We must mobilize for a deep transformation of the current economic system of production and consumption, while at the same time including protecting workers’ shop-floor concerns. We have to find a way of reconciling the interests of workers in energy-related industries and those of the working class facing the impacts of climate change.”

In short, the battle lines between labor and climate activists were drawn across five fields of action: speed, scale, scope, space and the state:

+ The unions – especially Numsa – wanted a slower transition to renewables due to fear the state won’t protect jobs.

+ Their ideal of the appropriate scale for electricity generation, grid transmission and distribution was always national, not the decentralized, “small scale embedded generation” strategies favoured by Climate Action neoliberals (the latter approach makes wide-scale electricity redistribution from rich to poor more difficult).

+ The scope demanded by unions is often narrower – in protecting existing dirty-energy jobs – but in Numsa’s case, it has also advocated for a more expansive post-capitalist vision.

+ The geographical dilemma – ‘space’ – is thorny, since the sunny, windy and tidal-power areas of South Africa generally don’t overlap with the inland coal fields and power plants, so CJ advocates found themselves challenged to address this disjuncture more explicitly.

+ Finally, there were diverging views of the role of the state, particularly the parastatal Eskom, since Numsa and other unions insisted on rescuing it as part of their explicitly socialist political agenda, while many citizens and CJ activists had already given up as a result of the energy agency’s deep-rooted corruption and pro-coal bias.

There are very few encouraging sites of joint work where these five divides in emphasis can be reconciled. The Million Climate Jobs approach to a Just Transition did not take root. Unions were too defensive. Many environmentalists – especially from the white middle classes – were unconscious of justice concerns.

Although in 2015 a major summit between Numsa, environmentalists and social movements addressed energy and climate change with great promise, at a time of consistent shortages and blackouts, there was no follow up. The summit declared opposition to “false solutions such as the introduction of nuclear energy on a huge scale, fracking, agrofuels/biofuels, carbon trading, ‘clean coal’ and carbon sequestration.” But the need for unifying, joint demands on the state for a Just Transition has, since then, yet to be explored, much less realized.

The working class does have a few cases where, if not production, at least the consumption of coal-generated power is being politicized. Perhaps the most climate-conscious urban social movement of the post-apartheid era was the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee, fighting a two-decade long struggle for energy justice. In part they were popular through encouraging 85% of the huge township’s residents to think of power as a ‘commons,’ hence illegally connecting electricity supply. They justified this in part because their visionary leaders regularly critique and protest Eskom’s coal-based generation. “For as long as Eskom uses coal, I won’t pay,” one leader told MSN news in March, refusing to change her stance “unless they connect us to the solar system grid.”

This then was, in 2019, the current unsatisfying hybrid-CJ politics unfolding. There was a mix of consumer-based pro-commoning militancy, in which the leading activists demanded that fossil fuels should be phased out and solar access made universal, combined with tough community struggles against the exploration, extraction, refining and combustion of coal, oil and gas. The leftist trade unions proposed radical versions of eco-socialism but defended their jobs with an understandable desperation. A burgeoning youth and ecologically-aware middle-class feinted towards CJ, but their stamina had not been tested. The mainstream Climate Action scene remained predictably tame and unambitious.

In this context, the vast majority of citizens were apathetic, and the upper-income elites lived in conditions akin to the richest First World habitats. These were the men and a few women who occupied the commanding heights of fossilized power, where profits and new discoveries were too sweet to kick their addictions – unless those promoting CJ politics became much better organized, and brave enough for the conflagration that inevitably lay ahead.