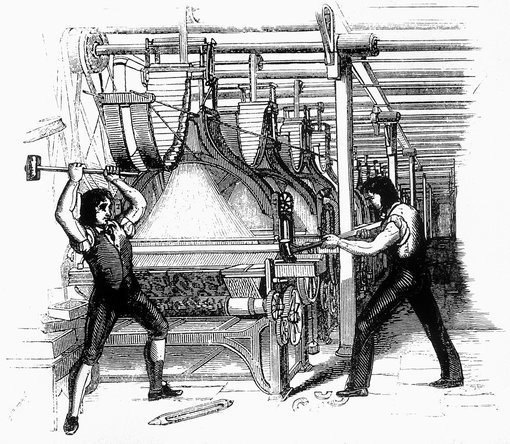

Frame-breakers, or Luddites, smashing a loom – Public Domain

In the fall of 1992, after I finished my second round of speeches for the Quincentennial of America’s “discovery,” drawing on my book about Columbus that had been published in 1990, I started on a book on a subject that had long fascinated me and I knew was just as timely as the Columbus book had been. It was a history of the Luddites, that group of workers in the mid-country of England who had resisted the onslaught of the Industrial Revolution in the early 1800’s by breaking offensive machines and had thus become the prototype of people who supposedly always resisted technology.

There had been no book published in this country telling the full story of the Luddites and only two books reprinted from meager English sources, so I knew that a book just now, when the internet was just beginning to be a means of communication beyond the scientific community that had developed it in the 1980’s, and computers were becoming ubiquitous, would certainly be needed.

And so I went to work, impelled by the need to give a sympathetic telling of the long-forgotten cause and a desire to put the Luddite tale of resistance to the machine before a public, given the increasing impact of the computer-created second Industrial Revolution then upon daily life, that might well might be in the mood to wonder about people who had suffered from the first. The book came out in the spring of 1995 to some modest praise and, from the mainstream press, some perplexity that anyone would want to bring up those people again, particularly because they had failed in their attempts to stem the tide of progress. And among a small but growing number of people, critics of the modern version of that tide who were beginning to call themselves “neo-Luddites,” it became what one of them called “the bible for our movement.”

I was not of course neutral in my retelling of the Luddite tale nor in using it as a theoretical guide in analyzing and castigating our contemporary economy. My analysis of this second Industrial Revolution ended this way:

Neither the means nor ends of this revolution make any pretense to nobility, nor does it claim to have a vision much grander than that of prosperity, perhaps longevity, both of which have seriously damaging environmental consequences. By and large its adherents would disclaim grand-sounding motives or methods, arguing them irrelevant: enough that progress may be presumed meritorious and material affluence desirable and longer life positive. If industrialism is the working-out in economic terms of certain immutable laws of science and technology, of human evolution, the questions of benign-malignant hardly apply. Those who want to wring hands at this inequity or that injustice are essentially irrelevant, whether or not they are correct: the terms of the game are material betterment for as many as possible, as much as possible as fast as possible, and matters of morality or appropriateness are really considerations of a different game.

Viewing the issue on its own terms, the question would then seem to come down to the practical one of the price by which the second Industrial Revolution has been won and whether it is too high, or soon will prove to be. The burden of this chapter is that there are no two ways of answering that question: the price, particularly in social decay and environmental destruction, has been unbearably high, and neither the societies nor ecosystems of the world will be able to bear it for more than a few decades longer, if they have not already been overstressed and impoverished beyond redemption.

To put it simply, modern technology enables us to do the bad things we’re doing faster and more efficiently than ever before.

You can imagine what the reaction of the champions of that Revolution must have been. Various Silicon Valley pundits were quick to denounce such heresy and among the crowd in California who had always looked favorably on technology—the patrons of the Whole Earth Catalog (an “access to tools” that prefigured the web) in the 1960’s—there was a feeling that a counterattack ought to be mustered as soon as possible.

It was in just such a role that one day in 1995 Kevin Kelly of Wired magazine in San Francisco called me in New York and asked for an interview. I had never heard of either one, but I agreed, went out and bought a couple of copies, and discovered that Wired was wide-eyed and indiscriminate in its love of technology and apparently blind to whatever downside it may have; Kelly, 42, was the executive editor. A few days later he came to my office in my apartment in New York’s Greenwich Village and set up a recorder to interview me.

He made no attempt to pretend impartiality, his questions were hostile from the first. But he let me lay out my ideas about the Luddites, about the relevance of their resistance to the machine, about the dangers that machines far more powerful than theirs were doing today and were likely to do in the coming decades. Kelly some years later said, “I was irked by his assertions of the coming collapse of civilization” and he challenged me to spell out in exactly which ways modern technology would likely cause the collapse of civilization as we know it—and when that would happen.

I was stumped for a bit because first of all it was hard to isolate just a few ways in which such a monumental catastrophe would come about and secondly I had given absolutely no thought as to when. Finally I blurted out “2020” because it had a nice familiar ophthalmological ring and at that time it seemed far, far away, and I tried to lay out in as succinct a way as I could how it could happen.

First, an economic collapse. I posited that it might take the form of a worldwide currency devaluation, in which the dollar loses its standing as the world’s reserve currency and becomes effectively worthless even in this country, and a global stock-market crash and depression.

Second, a political collapse, with upheavals both within nation-states and between. I saw the collapsed economy leading to maybe the bottom fifth of society in the developed world, no longer bought off with alcohol and drugs and celebrity and consumerism, rising up in rebellion and creating havoc and disarray throughout; at the same time a similar rebellion of the poor nations, no longer content to take the crumbs from the table of the rich, and simultaneously fighting violent guerrilla wars and flooding into the developed nations to escape their misery.

And finally, perhaps over-arching, an environmental collapse, in which global warming and ozone depletion, for example, made some areas like Australia and Africa unlivable and caused ice packs to melt, and old diseases, released from melting ice and deforested swamplands, mixed with new and spread deadly infections to all continents.

In truth, I had read a good deal on prognostications about future calamities—the Union of Concerned Scientists, for example, had issued a “warning to humanity” about “vast human misery” in 1992—but I had not before ever formulated them, never tried to be specific about the ways they would come about. So this was a first stab, quickly contrived and very imperfect, at what kinds of things I thought might befall the earth—nothing like what I could formulate just a decade later in another book.

It was enough for Kelly. With some sense of triumph, he whipped out a check for a thousand dollars and said, “I bet you US$1000 that in the year 2020, we’re not even close to the kind of disaster you describe.” He had obviously planned to maneuver me into this kind of challenge from the beginning. “We won’t even be close. I’ll bet on my optimism.”

Well, a thousand dollars in those days was a lot of money, period, and especially for me, a serious independent writer whose book sales were respectable but not spectacular. A thousand was about all I had in my checking account. But then I thought: what the hell, if I’m right, nobody is going to win a bet in 2020, and if I’m wrong the dollar still won’t be worth very much by that time.

I reached into my desk for the checkbook and quickly wrote out a $1000 check, dated March 6, 2020. I handed it to Kelly, shook his hand, and he said, “Oh, boy, this is easy money—but, you know, besides the money, I really hope I am right.”

After just a moment I said, “I hope you are right, too.”

We are now approaching that date—March 2020—and I thought it would make sense to see how close Western civilization has come to the predicted collapse in the year I predicted.

So I embarked on a book to find and assess the evidence.

It wasn’t hard to find environmental evidence—the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, whatever one thinks of its modeling abilities, has come up with lots of scary statistics and NASA and the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration gve confincing proof that the ten hottest years have been between 2005 and 2019 and the last five have been the hottest by far. Who cares what caused it, but such heat is sure to have dire effects on both lands and oceans.

As to political collapse, there are now 65 countries (a third of the world) fighting wars and in addition 638 conflicts between various insurgent militias, armed drug bands, and terrorist organizations, all this leading to nearly 300 million immigrants worldwide. And organizations that track these things say that there are now 76 nations in various stages of collapse, a dozen completely failed, and within even nominally stable nations unprecedented political rifts have caused violent street protests, legislative deadlocks, attempted coups (as here), and simply unworkable governments.

And the economic collapse that half the world’s economists are predicting would seem to include the consequences of unprecedented and ever-increasing debt (a global figure of $247 trillion), a worldwide move from the dollar to gold, an American banking system upheld by central bank money-printing, and financial inequality increasing blatantly at all levels, national to global.

Well, no, the collapse hasn’t come yet and I cannot give any guarantee that it will come in the next 12 months. But there is no doubt that industrial civilization is in a mess and collapse certainly does not seem impossible.

If I could find a publisher for this book, it would at least start to direct people’s attention to these crises and bring home the fact that they are all connected, interrelated so tightly that a failure at one point will bring failures at several others. It might also give people a chance to figure out how they will face the world when the collapse does happen.