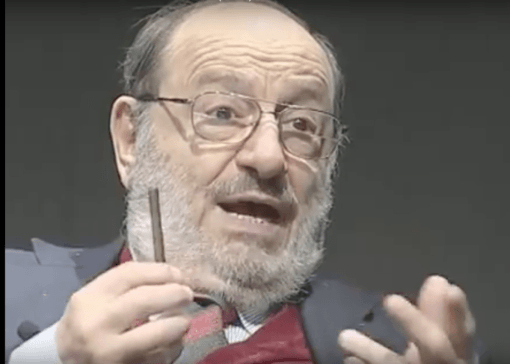

Umberto Eco at the University of Milan, 2014.

The famed author (The Name of the Rose) and semiologist, Umberto Eco, who so loved books, must have thought it his misfortune to live in a country whose people did not share his thirst for printed books. He was in fact avid for anything in print: books, antique or new, notebooks, manuals, ledgers, logs, while his fellow Italians are among Europe’s worst readers. Yet Eco was a world-acclaimed novelist, whom I had the good fortune of interviewing him for a Dutch magazine precisely in his heyday of fame and fortune: he wrote me a delightful fifteen-pages of answers in a written interview.

At one point in those pages Eco’s ever present irony emerges in his advice on “intelligent vacations”. Noting that “people who are not criminals or terrorists are more exigent in their recreational reading matter”, he made a series of suggestions: “People who want to keep up with Third World problems might consider the delightful Kitab al-s ada wa’l is’ad, by Abdul’l Al’Amiri, of which a critical edition of 1957 is available in Teheran. Or, the Zefir Yezirah; the Zohar naturally, for some good reading on the Cabalistic tradition. Or you can simply take along to the seashore Die Grundrisse, the apocryphal New Testament and some unpublished microfiches by the semiologist Peirce.”

Umberto Eco, writer, intellectual, philosopher, semiologist, sociologist, university professor, sometimes referred to as “the man who knows everything,” died on February 19, 2016 in his home in Milan at age eighty-four. His numerous books ranged from novels to wide-ranging books touching on most every aspect of the life of his times, plus countless academic papers and a weekly column for the leftwing Espresso magazine. His lectures at the University of Bologna were events where four hundred persons fought for space that no Italian intellectual could miss experiencing,

However books were Eco’s life: “A person who does not read lives one life, of maybe seventy years; the reader lives 5000 years,” he wrote.

I had the good luck of interviewing Umberto Eco in the year 2000, a text which however rings extremely current. His novel, The Name of the Rose of 1980 was the starting talking point. “My worst novel, he claimed.” But since the book deals with medieval abbey libraries which he loves he warmed to that subject.

“The library was born according to a design that has remained obscure throughout all centuries,” says the Benedictine Abbot in , The Name of the Rose.. “The book is a fragile creature,” the abbot adds, “it suffers from the use of time.” So in Eco’s mind the library must defend the fragile book. It must defend itself, unfathomable, like the truth it hosts. The fourteenth century Abbot calls his Benedictine Order a “reserve of knowledge that threatens to disappear in fires, sackings and earthquakes.”

In the pre-printing press centuries described by Eco, monastery libraries were vital centers of knowledge. But they were also shrouded in mystery because knowledge was already a dangerous thing. In reality most Monk scholars spent their time in the Scriptorum copying ecclesiastical books, illuminating, binding, and preserving them. Still, monasteries like the thirteen original ones founded by Saint Benedict in the sixth century in the mountains near Rome were Europe’s major reserves of culture during the subsequent barbarian invasions.

After Umberto Eco’s novel, I visited some of the monastery libraries. The Santa Scolastica Monastery in Subiaco is the only surviving one of the original Benedictine monasteries, concealed in the fabulous town of Subiaco isolated in the mountains seventy kilometers from Rome. Back then, its monks spent their time in meditation and copying books. Nothing dangerous then.

But the arrival in Subiaco 550 years ago of two German printers from Mainz—Arnoldus Pannartz and Conradus Sweynheym—changed monastery life. The printing press they introduced ended the work of illiterate monks who made the ink, prepared parchments from sheep skins, and bound the great books while the more learned copied books in artistic handwriting and artists illuminated the margins. Neither Paris nor Rome—soon to become Europe’s great printing centers—had yet begun when the Germans built their presses in isolated Subiaco and produced Italy’s first printed book: the philosophical-ethical work, the Lattanzio. Written by a 4th century convert to Christianity Cecilio Lattanzio, that book contains the first printed characters in Greek in the world—a type devised for its extensive quotes in Greek, all in mobile letters now called “Subiaco type.”

The book indicates Subiaco as the place of printing and is dated October 29, 1465.

The monastery, Sacro Speco, cut into the rocks, on various levels, nearly totally frescoed by eighth to thirteenth century artists, is one of the most spectacular but lesser known sites of Italy. An area of rugged mountains, narrow valleys, rushing waters, rocky cliffs and thick woods, Umberto Eco could have captured there the mysterious atmosphere of The Name of the Rose.

Umberto Eco’s novel was at the top of the USA Top Ten for months, sales around the world skyrocketed into many millions, and a film based on the work was made. The New York Times wrote of the phenomenon that “publishers should learn from this that the public is ready for something more than the usual prefabricated products.”

Literary critics around the world dissected The Name of the Rose, trying to solve the mystery of the novel’s extraordinary success. The book was labeled a historic novel, a theological thriller, a philosophic novel, a Gothic novel, a monumental exercise in mystification. Therefore, the author was criticized for his claim that the book was concocted artificially at the planning table and was assured of success from the start.

Eco agreed with the Italian critic and admirer, Beniamino Placido, that the book is only apparently a trip into medieval culture; behind its historic design, there blooms the history of the explosive tensions and the anxieties of the modern world. Eco wrote in the interview that “the Middle Ages are a mirror for the present. We find there the roots of our problems, of our anguish, of our crises.”

Moreover, he never believed in the old convictions of inspiration and passion in art. In the interview, he wrote: “People have not yet learned that every work of art is a game played out at the worktable. Nothing is more harmful to creativity than the passion of inspiration. It’s the fable of bad romantics that fascinates bad poets and bad narrators. Art is a serious matter. Manzoni and Flaubert, Balzac and Stendhal wrote at the worktable. That means to construct, like an architect plans a building. Yet we prefer to believe that a novelist invents because he has a genius whispering into his ear.”

When his novel appeared, Eco had already written some twelve works, from the poetics of Joyce to How to Write a Thesis. After having participated in a group of young, left-wing writers known as Gruppo 63, Italy’s major post-war literary movement, he was involved with leading participants of the 1968 protest movement, many of whom became the leaders of Italy’s left-wing terrorism. But he did not follow them into protest organizations or into politics.

When his novel appeared in 1980, Umberto Eco was already an internationally known scholar, a brilliant speaker and professor of semiotics, an expert in mass communications, essayist, journalistic writer, author, thinker; he was a super-gifted man with a fabulous memory. At age 48, he became a bestselling author overnight..

As a foreign correspondent in Italy, I reported on the Eco phenomenon. But before the novel appeared I had never read more than a few of his journalistic articles Though after his success, he stopped giving interviews—unless to the New York Times, Le Monde, or BBC, he agreed to a written interview with me because we had a close mutual friend in Milan, an antique book collector like Eco. However, his typed answers were some fifteen pages long.

If he belittles “inspiration,” Umberto Eco believed that the impulse to narrate is common to us all. “That’s why so many scientists and philosophers and critics, too, write novels. Not only those that we remember like Tolkien, Segal, Hoyle, Sartre, Asimov, and Harold Bloom, but many others we’ve forgotten. Writing is a way of revealing the contradictions of life that one would like to resolve. Writing fiction, like poetry, means simply to display those contradictions but not necessarily to resolve them. In fact, the reader, through his interpretive cooperation, decides what the story means.

“I wrote The Name of the Rose simply because I wanted to. A good reason. First comes the desire, like the desire to make love. Then one sits down at the worktable and begins, to play, to construct a possible world. The first year after I got the desire, I didn’t write, I designed, I made a plan of the abbey, I sketched out the list of names, I drew the faces of the characters. So I believe one writes a novel because of the desire to construct a world. And to communicate.”

Already in the 1950s, Eco was writing about the Middle Ages; his university dissertation was on St. Thomas Aquinas. In the explosive 1960s he worked for the major Italian publishing house, Bompiani. One said then that at editorial meetings, his was always the last word. Eco half closed his eyes, drew on his pipe, and spouted a phrase that resolved matters. In those years he was busy with “signs” and mass communications and became Italy’s leading semiologist. Even then anecdotes circulated that created a certain Eco image: Eco works twenty hours a day, Eco can quote from memory half of what he reads, Eco’s life is organized in a German way, he has an extraordinary ability to associate diverse things. He wrote me humorously that he also saves time by abbreviating interviews, then wrote those fifteen pages!

His success in the Chair of Semiotics at ancient Bologna University was immediate. His famous lectures were attended by hundreds of people, fascinated by his charisma. Narcissistic as he was, he responded by giving up to 250 lectures a year. Open to dialogue, he was by nature simultaneously ironic and academic. You never know, his friends said, if Eco is playing or working. He said he was an academic spider. The Eco style was severe but marked by jokes, games and memory contests. He was described as a “thinking machine.”

Since semiotics is easily applicable to the Middle Ages, so rich in signs and a less complex society, I asked him about his fascination with that period and its importance for the world today.

“The fashion for the Middle Ages, the medieval dream, cuts through all of European civilization. The Middle Ages were the crucible of Europe and modern civilizations: we’re still reckoning with things born then—banks and bank drafts, administrative structures and community politics, class struggles and pauperism, the diatribe between state and church, the university, mystic terrorism, trial based on suspicion, the hospital and the episcopate, the modern city, modern tourism, how one should respect one’s wife while languishing for one’s love—because the Middle Ages also created the concept of love in the West. “

Eco had views on everything that has happened since the Middle Ages. He mused on what a library should and should not be. He said that he especially liked the Sterling Library at Yale—a neo-Gothic monastery, he called it. He deplored the labyrinth-like libraries of Italy and advanced theoretical organizational plans for an ideal library.

He described how clothes condition man, recalling how “warriors in past centuries dressed in armour lived exteriorly, while monks had invented a dress—majestic, fluid, all of a piece—that left the body free and forgotten (inside and under!). Monks were thus rich in interior life, and filthy because their bodies, defended by a dress that while it ennobled the body, also liberated it to think and forget itself.”

He reflected on how much it costs to write a masterpiece, from expensive works like Magic Mountain (sanatorium, furs, etc.) to Death in Venice (Lido hotels, gondolas and Vuitton bags) to cheap works like For Whom the Bell Tolls (clandestine trip to Spain, room and board furnished by Republicans, and sleeping bag with girl), or Robinson Crusoe (just embarkation costs).

I have listed Eco’s diverse subjects also to entertain but also to underline his predilection for lists. His subjects made up a long list. His mind catalogued, transformed and applied. I asked him why all those lists in The Name of the Rose.

“I’ve always loved the technique of the list. For many years I made a collection of examples and considered writing a book on the use of lists, from classic literature down to Joyce. Moreover, the list is a typical medieval descriptive strategy. Therefore, I used the list in this book because it is so medieval.

“In the tendency of the list there is something even more important: it is typical of both primitive and overly cultivated epochs. When one doesn’t yet know, or no longer knows what is the form of the world, instead of describing a form, one lists its aspects. One proceeds by aggregation instead of by organization. In substance, my character Adso in The Name of the Rose does not understand well what is happening nor what has happened; therefore, he lists what he sees or what he hears, and what he believes to have seen—and he knows only because he has heard or read other lists.”

Umberto Eco was the intellectual per se. He was considered such in Italian and in international society. His analogy between the intellectual and the critic is a cogent reflection of the role he saw for himself in society. “I often say that the intellectual is something like Italo Calvino’s Baron Rampante: he sits in the trees but follows and criticizes things, thus participating in the events of his era. The intellectual’s participation in political life is a critical activity that sometimes can assume forms of apparently disinterested research, even if as a private citizen he can be both committed in public life and able to put his knowledge at the disposition of a party or a group. But his true intellectual function is exercised not when he speaks for his party or group but when he speaks against it. It’s easy to criticize enemies. The problem is to criticize friends. The role I play is of one who through his analyses signals something that is not functioning, in areas where too little has been said.

“Yet, I try to remember that while society needs its poets and wants to hear their opinions, it’s however a false position. Poets speak through their works and are worth little at conferences where they usually say stupid things. My success as a novelist gives me a halo of authority but when I do agree to speak I try to speak as an essayist not a novelist.”

Finally among the interview written questions I asked Eco about power relationships, which he claimed were the background for The Name of The Rose. “The role of European intellectuals was powerful in the post-WWII era. Europe was coming out of war and Fascism and was politically split down the middle between progressives (Socialists and Communists) and Conservatives (Fascists and Christian Democrats). Progressive intellectuals were at the heart of the protest movements of 1968 in Italy, France and Germany. The question of power was paramount.”

Eco found that Michel Foucault elaborated the most convincing notion of power—pouvoir or potere—in circulation. “Power is not only repression and interdiction but is also incitement to speak and the production of knowledge. Secondly, power is not one single power. It is not massive. It is not a unidirectional process between one entity that commands and its subjects. Power is multiple and ubiquitous. It is a network of consensuses that depart from below. Power is a plurality. Power is the multiplicity of relationships of strength. For the semiologist, language is always closely linked to power.”

Eco’s theory was that “the criticism of power has degenerated because that criticism has become massive. Mass criticism of power spawned ingenuous notions that power—the system—had one center, symbolized by the evil man with a black moustache manipulating the working class.” As an example of the misunderstanding Eco recalled theorists of European terrorism who wanted to strike at the heart of the state.

“The danger,” according to Eco, “is confusing power and force. Force is causality. And causality is reversible. That reversal is called revisionism. On the other hand, to change power is to make a revolution. For example, man decides that woman will wash the dishes—a symbolic relationship of force based on the consensus of the subject. That relationship is changed if the woman refuses to wash the dishes—that is revisionism. Compromises are revisionistic. Revolution, however, is the sum total of a long series of revisions, the violent overturn of progressive revisions. Society becomes a universe devoid of a center. Everything is periphery. There is no longer the heart of anything. Only romantic terrorists of the Red Brigades thought that the state had a heart and that the heart was vulnerable.

“On the other hand, multinational empires exist today. They are not an invention of protesters or terrorists. I don’t want to moralize and say that multinationals are bad. They are the form that modern industrial organization has taken in capitalistic society. It’s also true that multinationals are always disturbed by local events and local political decisions. Look at what happened in Chile. And now in many places. This is one of the problems of our times. Don’t ask me for a solution. I just note it.”