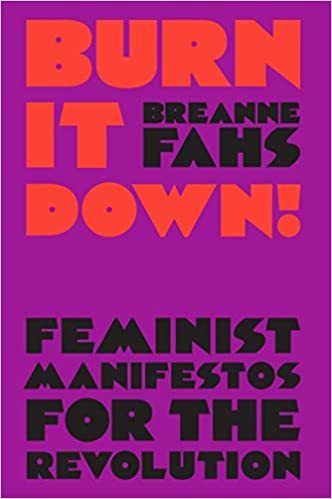

Webster’s defines a manifesto as “a written statement declaring publicly the intentions, motives, or views of its issuer.” In her recently published book Burn it Down! Feminist Manifestos for the Revolution, editor Breanne Fahs notes that although the manifesto form began with nobles and kings who used them to tell their subjects how things were, the form has become associated with the Left and the street, so to speak. They are urgent, strident and occasionally nihilistic; contradictory and rabble-rousing. The best known of all manifestos is probably the one written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels—The Communist Manifesto. In this reviewer’s mind, that work is one of the most powerful and concise pieces of text every published. Its purpose is clear in the first paragraph. The rationale it presents is as flawless and simple as an elementary school math problem. That pamphlet is the ultimate template for the form we call the manifesto.

On the other hand, the word feminism has no clear template, no text that exemplifies its essential meaning. To the modern liberal, feminism means, among other things, the right of women to compete equally in the capitalist economy she exists in. This same woman—whose bourgeois reality is assumed in the fact she is even competing—also means she has the right to choose who she sleeps with and whether or not she will have children. According to this definition, her destiny is as wide open as men in her position believe theirs is. The modern right winger accepts a similar definition. This means that they understand women are in competition with men. That understanding usually results in two main behaviors. One is filled with resentment which results in attempts to restrict women to their home and their children. The other is also tinged with resentment but accepts that certain women are of use to the power structure in roles allowed them by the male power structure. Both of these positions never accept that women are as capable as men assume themselves to be.

Burn it Down! Is about another kind of feminism. It is a feminism that rejects capitalism and its sexist core. It is also a feminism that transcends the conventional and assumes nothing is as it was before. The manifestos range in time from Sojourner Truth’s “I Am as Strong as Any Man” published in 1851 to the 2018 Susan Stenson tract titled “Occupy Menstruation.” From Valerie Solanos 1967 SCUM Manifesto to Bikini Kill’s Riot Grrl Manifesto of 1991. However, the bulk of the entries are from the period known historically as the second wave of feminism, which ran from the mid-1960s through the 1970s. It is that period which brought issues of race and non-heterosexuality into a discussion which to that point had been one focused mostly on the lives of white-skinned bourgeois western women. The numerous manifestos, poems, and rants from that period in this book address each and every one of these permutations from a multitude of vantage points—every single one of them radical and some revolutionary. This latter aspect can be attributed to the spawning grounds for this second wave of feminism—the New Left and the counterculture. While both of these movements were certainly male-dominated and heterosexist, it was the first stirrings of liberation and the consequent frustrations they provided to women that caused them to take a closer look at their situation.

As I read this text, bouncing from one manifesto to the other, I was struck by at least two phenomena. One thing that struck me was how familiar I was with many of the texts. I would argue that this familiarity is proof of the influence they had on those of us in the aforementioned movements (especially the Left). The other phenomena that hit me was how little some things have changed. Women are still fighting for equal pay and the right to choose their own destinies. Non-white immigrant women are still near the bottom of the economic and social order in the United States. Most Black women are right there with them. And most white middle-class women are still seeing their fight for equality as one that involves them competing with white men for the right to exploit and oppress those whose class and skin tone they do not share.

There are newer expressions of feminism printed in this text, too. Like the earlier manifestos, they are radical; anti-capitalist, anti-gender discrimination, and calling for a new social and sexual order. Also like the earlier submissions, some focus on capitalism and its well-documented shortcomings while others point their pen at sexuality and its meanings in the twenty-first century. This text is important historically and as a handbook for understanding and organizing today. Fahs has put together a collection that runs from the immediate and practical to the futuristic and abstract. In doing so, she reminds us that radical feminism is both utopian vision and practical argument.